Penumbra

At The Old Stone House Brooklyn, NY 2023-24

In “Picturing the Constitution” curated by Katherine Gressel

Penumbra (def. A partial shadow, as in an eclipse, between regions of complete shadow and complete illumination) is a multi-part project and installation that challenges the constitutionality of Dobbs v. Jackson, a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, June 24, 2022, in which the court held that the Constitution of the US does not confer a right to abortion. In the Constitution, the penumbra includes a group of rights implied from other explicitly protected rights in constitutional provisions. Found in the 1791 Bill of Rights, Ninth Amendment, the term first gained attention in 1965, when the Griswold v. Connecticut decision cited it to identify a right to privacy that would allow married couples to use contraception.

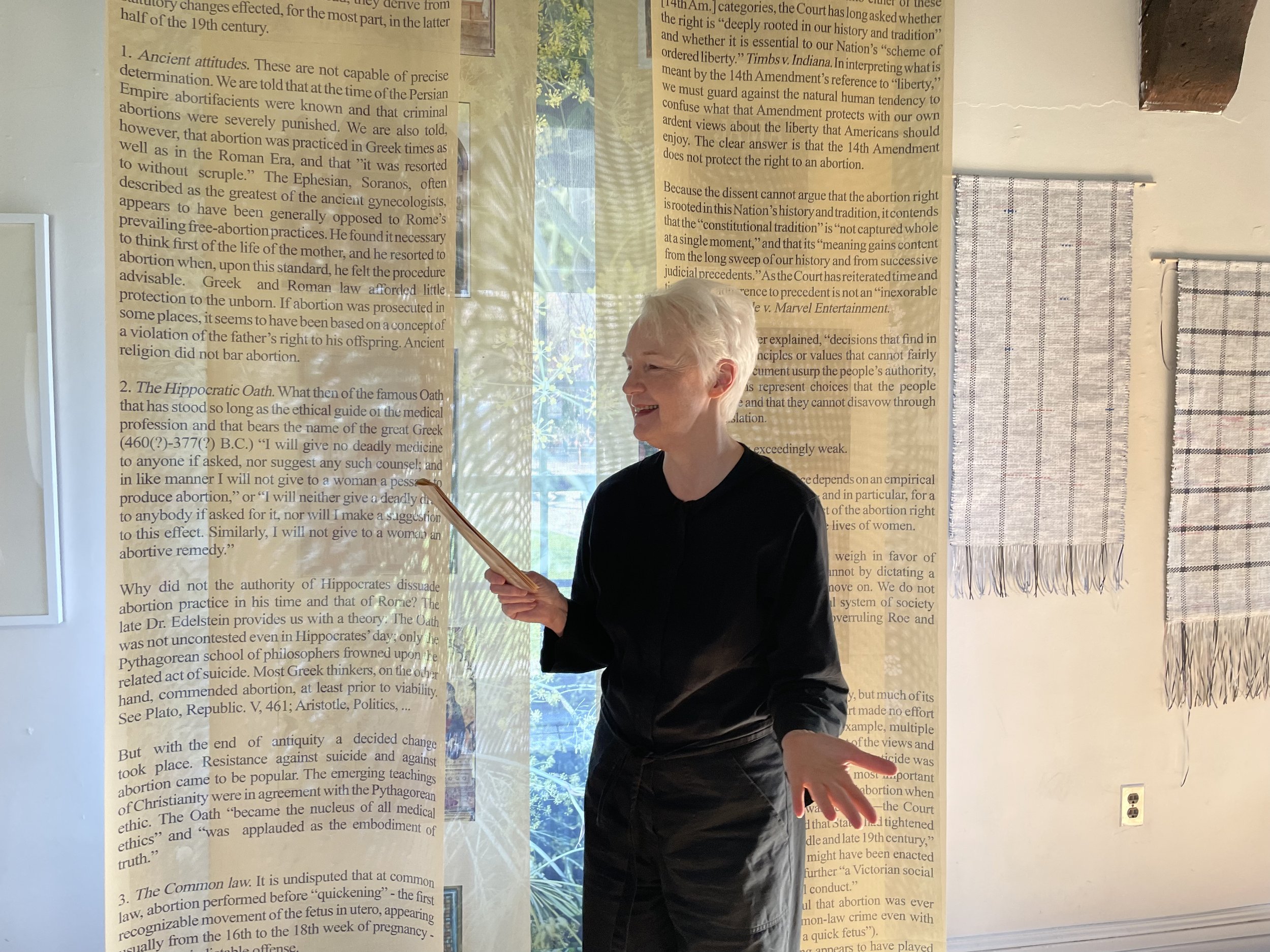

Detail of Penumbra Installation at the event “Penumbra Kit: A Workshop on Reproductive Rights and the Constitution”.

When the Dobbs decision calls attention to the phrase ‘(not) deeply rooted in our history and tradition’ to explain why abortion was not a right granted in the Constitution, we ask ‘whose history….whose tradition?’ Our answer is abortion history is women’s history as we draw attention to the millennia-long legacy of women using herbs for abortion and contraception, a ‘birthright’ that is part of a deeply hidden, repressed and often destroyed global practice.

Installation view of Penumbra in “Picturing the Constitution” at the Old Stone House.

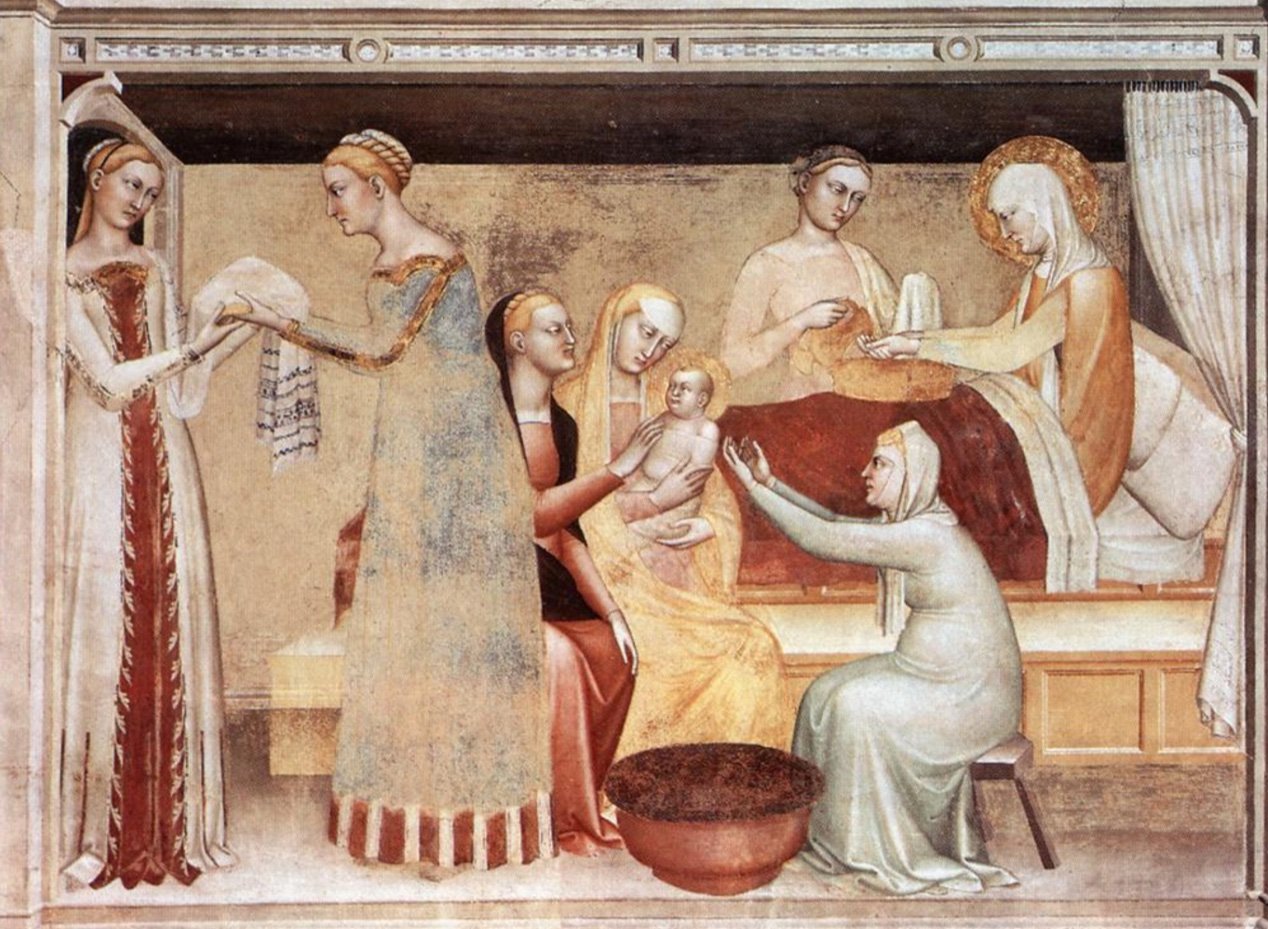

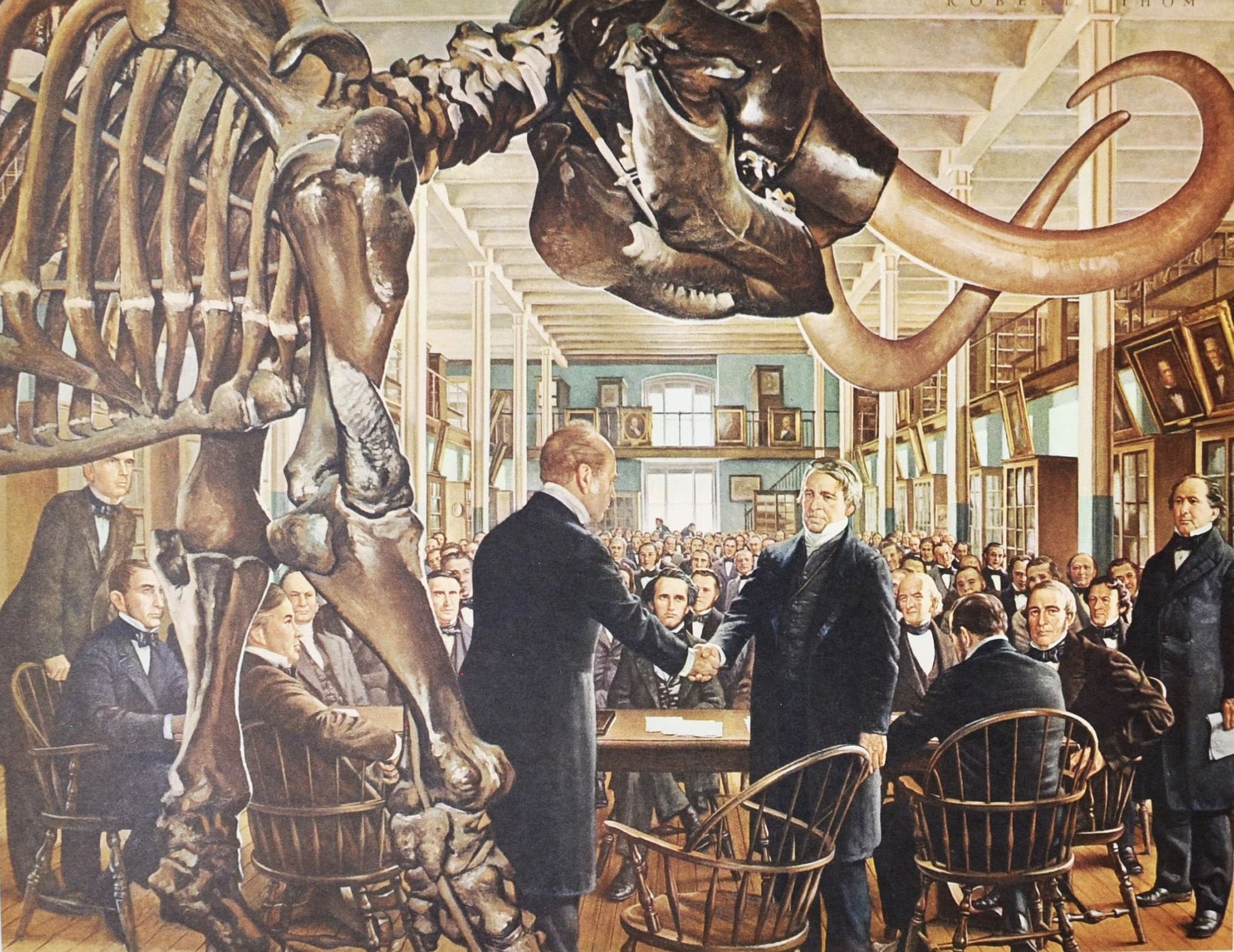

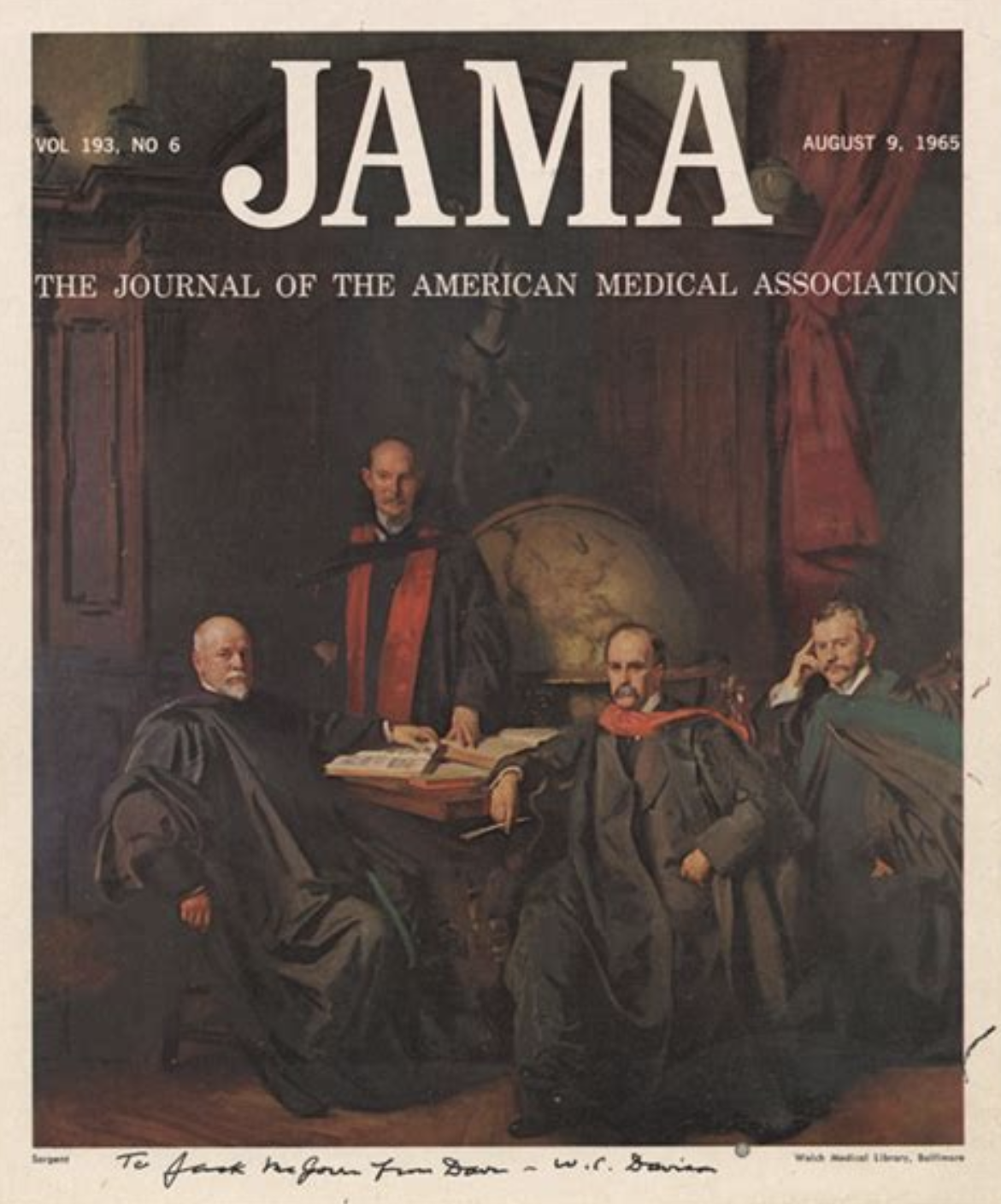

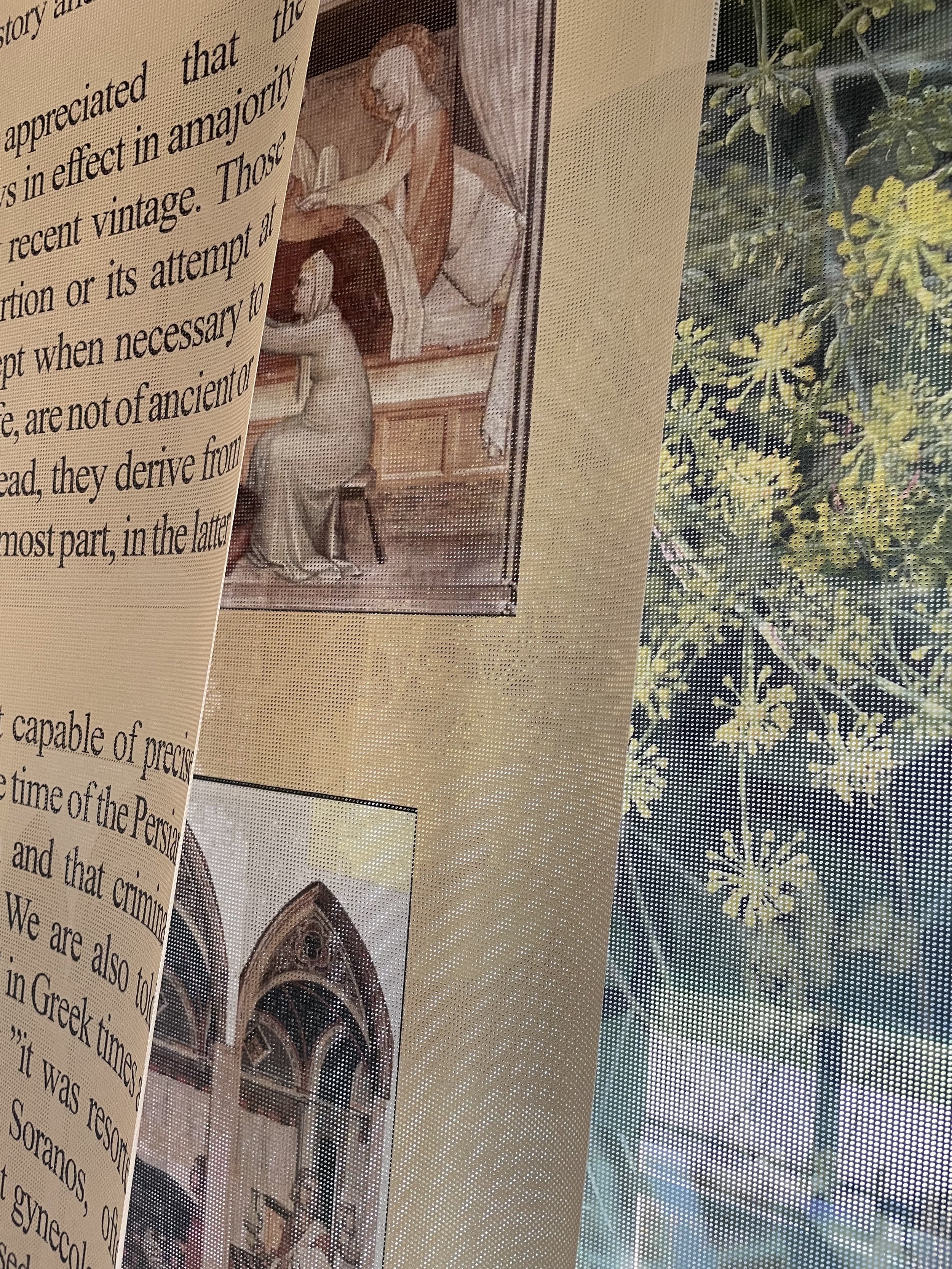

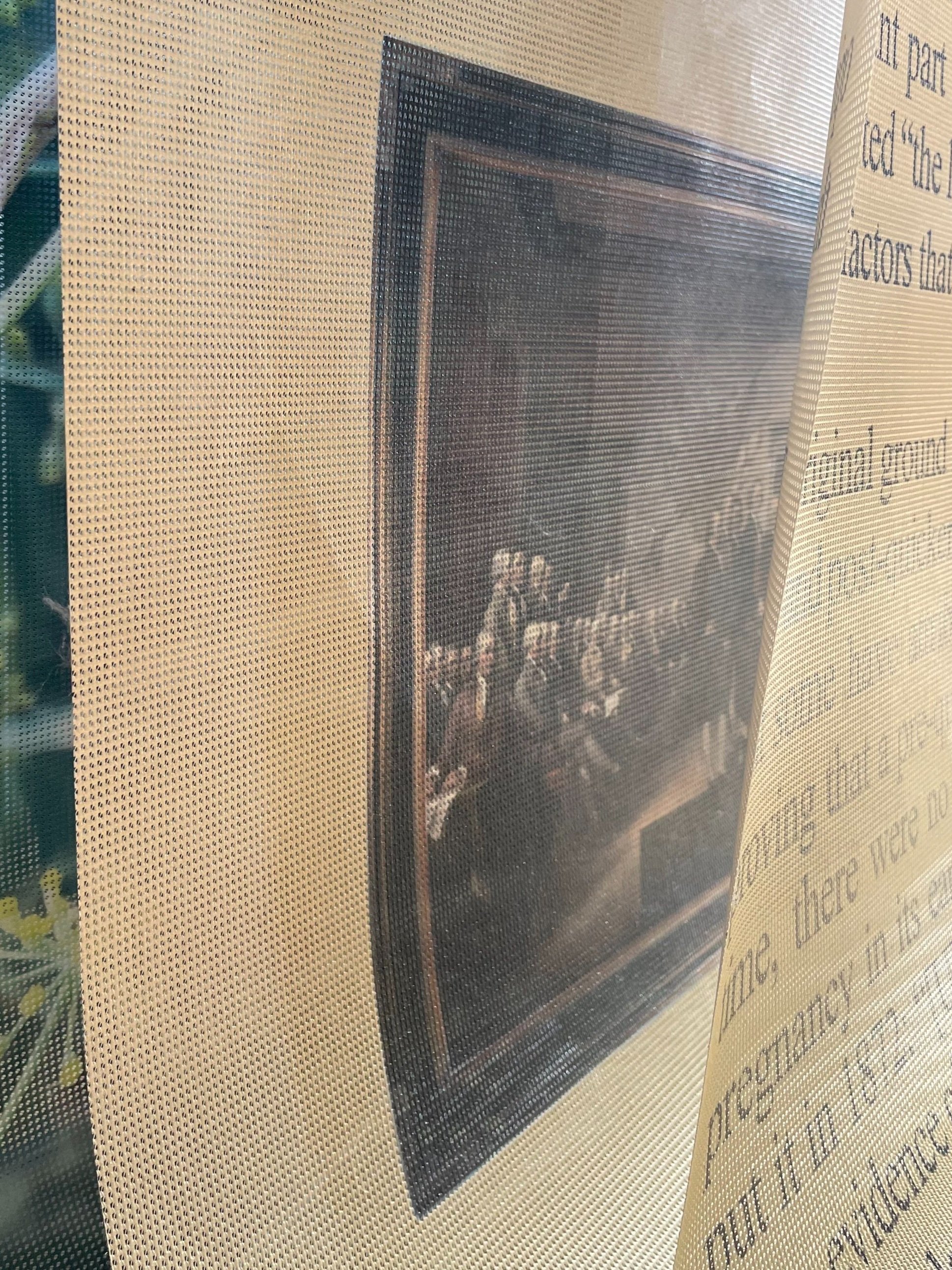

Here we present a two panel, multi-layered curtain on a window overlooking the gardens of Washington Park. On the right hand panels we juxtapose selected text from Dobbs, placed on a background of images of groups of ‘men making serious decisions’. On the left hand panels selections from Roe are placed on a background of women taking care of other women. Both sides are placed against a background of images of herbs used for abortion and contraception.

Renderings of the 3 Penumbra panels

These slides reveal the images that are partially obscured by the top layer of text in the installation.

+ Expand the sections below to read the texts. Or see the Penumbra Booklet (view/download pdf)

-

It perhaps is not generally appreciated that the restrictive criminal abortion laws in effect in a majority of States today are of relatively recent vintage. Those laws, generally proscribing abortion or its attempt at any time during pregnancy except when necessary to preserve the pregnant woman's life, are not of ancient or even of common-law origin. Instead, they derive from statutory changes effected, for the most part, in the latter half of the 19th century.

1. Ancient attitudes. These are not capable of precise determination. We are told that at the time of the Persian Empire abortifacients were known and that criminal abortions were severely punished. We are also told, however, that abortion was practiced in Greek times as well as in the Roman Era, and that 'it was resorted to without scruple’. The Ephesian, Soranos, often described as the greatest of the ancient gynecologists, appears to have been generally opposed to Rome's prevailing free-abortion practices. He found it necessary to think first of the life of the mother, and he resorted to abortion when, upon this standard, he felt the procedure advisable. Greek and Roman law afforded little protection to the unborn. If abortion was prosecuted in some places, it seems to have been based on a concept of a violation of the father's right to his offspring. Ancient religion did not bar abortion.

2. The Hippocratic Oath. What then of the famous Oath that has stood so long as the ethical guide of the medical profession and that bears the name of the great Greek (460(?)-377(?) B.C.), who has been described as the Father of Medicine, the 'wisest and the greatest practitioner of his art,' and the 'most important and most complete medical personality of antiquity,' who dominated the medical schools of his time, and who typified the sum of the medical knowledge of the past? The Oath varies somewhat according to the particular translation, but in any translation the content is clear:

“I will give no deadly medicine to anyone if asked, nor suggest any such counsel; and in like manner I will not give to a woman a pessary to produce abortion,” or “I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody if asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect. Similarly, I will not give to a woman an abortive remedy.”

Why did not the authority of Hippocrates dissuade abortion practice in his time and that of Rome? The late Dr. Edelstein provides us with a theory: The Oath was not uncontested even in Hippocrates' day; only the Pythagorean school of philosophers frowned upon the related act of suicide. Most Greek thinkers, on the other hand, commended abortion, at least prior to viability. See Plato, Republic, V, 461; Aristotle, Politics, …

But with the end of antiquity a decided change took place. Resistance against suicide and against abortion became common. The Oath came to be popular. The emerging teachings of Christianity were in agreement with the Phthagorean ethic. The Oath “became the nucleus of all medical ethics” and “was applauded as the embodiment of truth.”

3. The Common Law. It is undisputed that at common law, abortion performed before “quickening”- the first recognizable movement of the fetus in utero, appearing usually from the 16th to the 18th week of pregnancy was not an indictable offense.

Whether abortion of a quick fetus was a felony at common law or even a lesser crime is still disputed.

4. The American Law. In this country the law in effect in all but a few states until the mid-19th century was the pre-existing English common law.

It is thus apparent that at common law, at the time of the adoption of our Constitution, and throughout the major portion of the 19th century, abortion was viewed with less disfavor than under most American statutes currently in effect.

-

Constitutional analysis must begin with the language of the instrument, Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1, 186-189. The Constitution makes no express reference to a right to an abortion.

In deciding whether a right falls into either of these [14th Am.] categories, the Court has long asked whether the right is “deeply rooted in our history and tradition” and whether it is essential to our Nation’s “scheme of ordered liberty.” Timbs v. Indiana, 586 U.S. _ , _ (2019) (Slip op., at 3); McDonald, 561 U.S., at 764, 767; Glucksberg, 521 U.S., at 721. In interpreting what is meant by the 14th Amendment’s reference to “liberty,” we must guard against the natural human tendency to confuse what that Amendment protects with our own ardent views about the liberty that Americans should enjoy. The clear answer is that the 14th Amendment does not protect the right to an abortion.

The original ground for drawing a distinction between pre- and post-quickening abortions is not entirely clear, but some have attributed the rule to the difficulty of proving that a pre-quickening fetus was alive. At that time, there were no scientific methods for detecting pregnancy in its early stages, and thus, as one court put it in 1872: “[U]ntil the period of quickening there is no evidence of life; and whatever may be said of the feotus, the law has fixed upon this period of gestation as the time when the child is endowed with life” because “foetal movements are the first clearly marked and well defined evidences of life.” Evans v. People, 49 N.Y. 86, 90 (emphasis added); Cooper, 22 N.J.L., at 56 (“In contemplation of law life commences at the moment of quickening, at that moment when the embryo gives the first physical proof of life, no matter when it first received it” (emphasis added)).

Because the dissent cannot argue that the abortion right is rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition, it contends that the “constitutional tradition” is “not captured whole at a single moment,” and that its “meaning gains content from the long sweep of our history and from successive judicial precedents.” As the Court has reiterated time and time again, adherence to precedent is not an “inexorable command.” Kimble v. Marvel Entertainment, LLC, 576 U.S. 446, 455 (2015).

As Justice White later explained, “decisions that find in the Constitution principles or values that cannot fairly be read into that document usurp the people’s authority, for such decisions represent choices that the people have never made and that they cannot disavow through corrective legislation.

Roe’s reasoning is exceedingly weak.

Any intangible form of reliance depends on an empirical question that is hard for anyone - and in particular, for a court - to assess, namely, the effect of the abortion right on society and in particular on the lives of women.

Traditional stare decisis do not weigh in favor of retaining Roe or Casey; Court cannot bring about the permanent resolution of a rancorous national controversy by simply dictating a settlement and telling people to move on. We do not pretend to know how our political system of society will respond to today’s decision overruling Roe and Casey.

“Appendix”

Roe featured a lengthy survey of history, but much of its discussion was irrelevant,

and the Court made no effort to explain why it was included. For example, multiple paragraphs were devoted to an account of the views and practices of ancient civilizations where infanticide was widely accepted. When it came to the most important historical fact—how the States regulated abortion when the Fourteenth Amendment was adopted—the Court said almost nothing. It allowed that States had tightened their abortion laws “in the middle and late 19th century,” but it implied that these laws might have been enacted not to protect fetal life but to further “a Victorian social concern” about “illicit sexual conduct.”

(“[I]t now appear[s] doubtful that abortion was ever firmly established

as a common-law crime even with respect to the destruction of a quick fetus”). This erroneous understanding appears to have played an important part in the Court’s thinking because the opinion cited “the lenity of the common law” as one of the four factors that informed its decision.

During the Penumbra workshop participants were invited to explore the layers of the installation and the exhibition as a whole. They were introduced to a women’s history of abortion through a paper delivered by Maureen Connor.

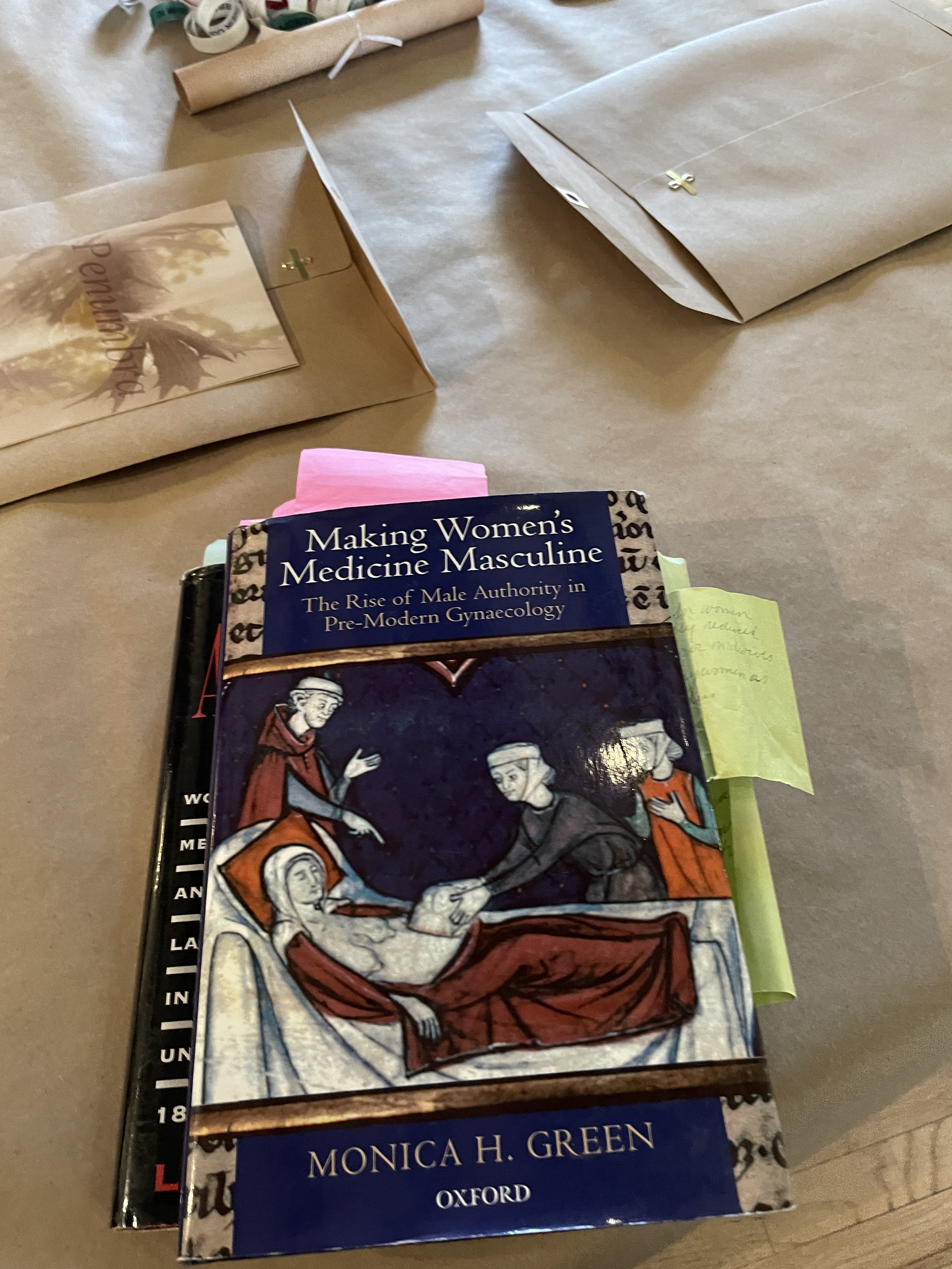

The workshop space included books, herbs, and the contents of the Penumbra Kit: a booklet on the project, resource lists, and a copy of the case study, A Place for Herbal Abortion in Clinical Herbalism by Daena Horner, Molly Dutton-Kenny, Ember Peters, Chere Suzette Bergeron, Amanda Jokerst in Journal of American Herbalists Guild Vol 21 / 2 Fall 2022. (view / download pdf) Tables also included materials for the exercise led by Jason Leggett.

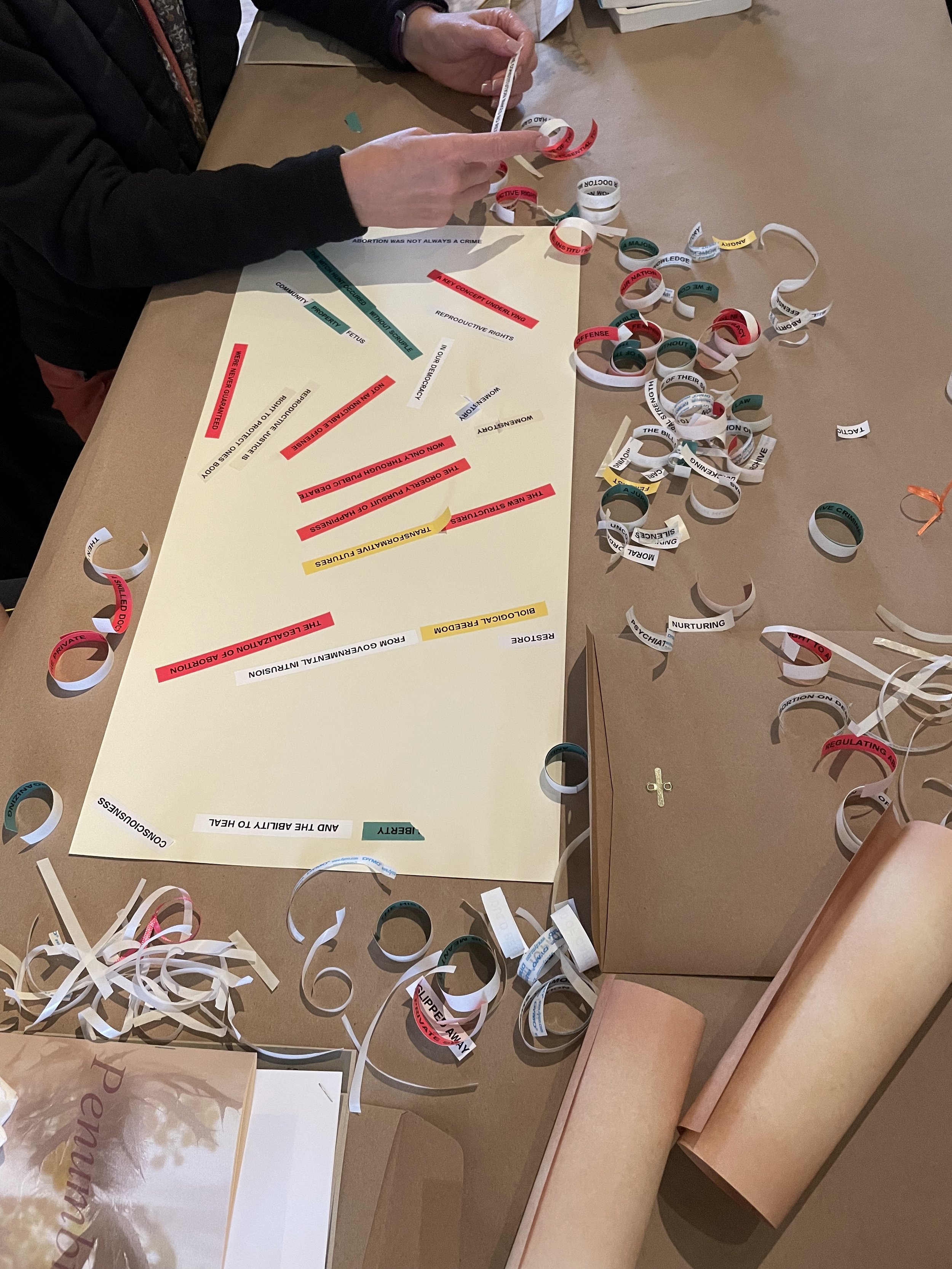

Jason Leggett engaged the participants at each table in a group exercise involving collaborative construction of a text made from fragments selected from Roe v. Wade and Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, as well as other abortion related cases and other sources.

Working with the same sets of text, each group constructed meaning through both play and serious dialogue. A guided discussion involved sharing the composite texts and drawing comparisons.

+ Expand the section “the restrictive criminal abortion laws” to explore the texts the groups worked with.

-

in effect in a majority of states today

are of relatively recent vintage

liberty finds no refuge in a jurisprudence of doubt

It was resorted to without scruple

At common law

Not an indictable offense

the institution of the family

is deeply rooted in this Nation's history and tradition

one of the vital personal rights essential to

the orderly pursuit of happiness

it is essential to our Nation’s

scheme of

ordered liberty

The right to abortion

The Constitution makes no reference

Due Process Clause protects two categories of substantive rights

in our democracy

by citizens trying to persuade one another

a penumbra where privacy is protected

from governmental intrusion

specific rights would be less secure

peripheral rights

The Bill of Rights is

the primary source of expressed information

as to what is meant by constitutional liberty

nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property

If we consider the historical context in which

the witch-hunt occurred

the gender and class of the accused

and the effects of the persecution

then we must conclude

that witch-hunting was an attack on women’s resistance

to the spread of capitalist relations

power that women had gained

by virtue of their sexuality

their control over reproduction and

the ability to heal

Another doctor won’t look at me

Doctor will not take the case

Psychiatrists were among the first to question

the new structures

regulating abortion

In the early 1950s

a skilled doctor or a butcher

Women themselves had taken out of the private

and into the public

Women’s reproductive rights were never guaranteed

in the private sphere

a key concept underlying the legalization of abortion

won only through public debate

political organizing

coalition building

collective action

problems

tactics

strategies

consciousness

uncovering women’s hidden histories

important knowledge

should be

library

archive

how to perform an abortion

reproductive justice is women’s history

abortion is women’s history

Abortion on demand

right to protect one’s body

self-defense

silence

speaking

for

the

quickening

Abortion was not always a crime

feel the fetus

moving

slipped away

restore

nurturing

community

care

moral strength

moral order

reproductive rights

The creation of Penumbra involved many months of consultation and process between law professor Jason Leggett and conceptual artist Maureen Connor. The project received additional support from Social Practice CUNY (SPCUNY), an educational network that fosters interdisciplinary exchange among socially engaged affiliates of the City University of New York (CUNY).